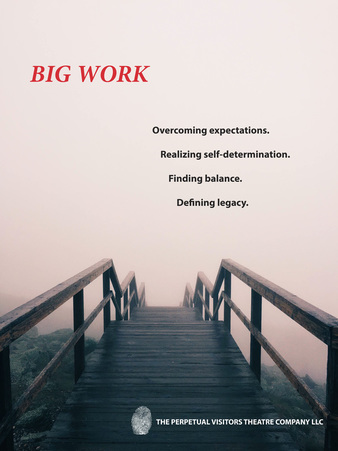

By Kate Ask any writer and they will tell you they become attached to their characters. But documentary work adds another layer to it. When you’ve sat across the table from someone who has opened up to you about their lives, choosing not to include what they’ve told you in the piece you’re writing feels like you are somehow saying her story is less important than someone else’s story. Transforming the 138,097 words from our interview transcripts into Big Work, a 16,000 word dramatic piece, has led to incredibly tough choices about what material to use and what to let go of. Essentially, we could use only 10 percent of the stories we collected in our final piece. Sometimes this meant letting go of a moment or observation we love; other times it has meant not including whole interviewees as characters. And while Melissa and I know having too much good material is a much better problem than not having enough, the cuts have been surprisingly painful. But we can’t ask an audience to sit through a 12-hour play, and the piece as a whole needed direction and cohesion in addition to containing great individual stories. Here is how Melissa and I went about choosing what to include. 1. We asked ourselves, “What is each interviewee’s core struggle with work?” Before we started writing the script, we spent several weeks just reading and re-reading every transcript. While each interviewee shared complex feelings about their jobs in relationship to their lives and their identities, each person seemed to have one thing they were wrestling with above all else. We challenged ourselves to try and name the struggle for each interviewee in one word. When Melissa and I met to discuss the words we had chosen, we discovered that some of the themes we initially set out to examine in relationship to our work – gender, age, immigration status – were too narrow. Instead we saw people, regardless of those labels, struggling with one of four things: to overcome expectations, to realize self-determination, to find balance, or to define their legacy. Naming these struggles not only helped us to understand who our characters are, they also provided the structure for our piece. These themes became the scenes of our play. 2. We eliminated everything that wasn’t directly related to a character’s core struggle or essential biography. There was a man I interviewed from Nigeria who told me so many fascinating stories about what it is like to be an immigrant working in the United States, and particularly the ways he feels an immigrant approaches college differently than American-born students. I loved these passages, and was reluctant to let go of them. But when I started asking myself about what he was really concerned with, it was clearly his legacy. When given the chance to direct the conversation, he spoke about trying to find work that is meaningful and that leaves something behind. He had only spoken about being an immigrant because I had asked him directly about it multiple times. I’m working on a play that asks people how they identity themselves, but I was labeling him and asking him questions that weren’t particularly relevant to his journey. By keeping only what was at the heart of each person’s struggle, we eliminated a lot of anecdotes. But more importantly, we have clearer, richer characters engaged in more meaningful discussions with one another. 3. We looked for characters who offered similar stories. There was no way to include meaningful characters based on all 40 people we interviewed without this being a series and not a single piece (which we considered). After we re-read the transcripts, we found that several characters were wrestling with the same things, had similar biographies, or articulated similar frustrations and triumphs. Melissa and I look at each of those stories and see their value. We see the individuality of the person who told it, and we took a lot away from having heard each one. But for the sake of drama, our global story didn’t need two characters saying the same thing. So we eliminated duplicates, and included stories from only 26 of our interviewees (which admittedly is still a lot). It can be a struggle for Melissa and me as we continue to tighten and hone our play because we know everything that didn’t make it into the final script. There are moments and stories we love that just didn’t have a home here, and we will always know they aren’t there. Hopefully, if we’ve done our jobs, audiences won’t feel those gaps. We’ve had to remind ourselves many times that we can use these interviews to create other pieces, maybe even a couple of 10-minute plays. But while these choices have been difficult, what has surprised us most of all is that we actually found the voice of this piece – really our voices – from the struggle to let go. It made us examine characters in more depth, ask tougher questions, and debate the themes that arose against our original hypotheses of what we would find. Shaping these interviews into a larger story about work and life in America has been an extraordinary journey, and one I wouldn’t trade for anything. We can’t wait for the next phase when we get to have these conversations with our actors, and then with you.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

ARCHIVES

July 2016

WHAT YOU'LL FIND HEREStory inspirations. Artist reflections. Community conversations. CATEGORIES |

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed