By Melissa Can we make art that we are passionate about, nurture that art to the public eye, and live balanced, sane lives while we do it? That is the grand life experiment that Kate and I embarked on when we decided to usher our first documentary piece Big Work into the world. It hasn’t always been easy. If you have been following us on social media or the blog, you probably noticed that we rescheduled our workshop reading of Big Work from November 2015 to March 5, 6, and 7, 2016. Plays are postponed all the time, usually because of something negative – a major casting issue, a challenge finding rehearsal and performance space, or a problem with funding. Fortunately, our decision wasn’t driven by anything negative; we were simply having too much fun to be rushed or to allow this play to become something on a checklist in our “busy” lives. Really? Too much fun working on a script? How can that be possible? Aren’t artists supposed to thrive on the pain of producing work? And we’re talking about having too much pleasure to want to rush? When we founded The Perpetual Visitors Theatre Company, we spent a lot of our time talking through not only the kind of theatre we wanted to make, but also the way that we wanted to make theatre. Although we don’t elaborate too much about this belief on our website, these values drove not only our decision to postpone, but pretty much everything we do. 1. We wish to dismantle the belief that artists need to be tortured and the creative process needs to be painful. Regardless of whether you are a musician, actor, writer, or creative of any kind, we can all agree that somewhere in our collective history, we decided that to be a “serious artist” meant you have to suffer for your art. Yes, the creative process has its ups and downs, and of course, there are challenges to be met along the way. But in the end, isn’t it vital to derive pleasure from whatever glorious, beautiful thing you are making? We think so, and we’re not afraid to let everyone know that crafting this play has been one of the great pleasures of our recent lives. We are daring to love our play and our process, and we are daring to savor it. 2. We believe that the way we make art is just as important as the art we make. As human beings and as artists, Kate and I have had countless conversations about how process is equally important as product when it comes to creating. Often when we make something, there is a gap between what we say we value and what we do in action. It has been our goal from the start to be very mindful of this during our process. For example, if you are working on writing a book about health, balance, and spiritual awakening, but allow the creation process to deprive you of sleep, joy and peace of mind, aren’t you defeating your own purpose? Similarly, we are striving to create a play that explores our relationship to our jobs and the rest of our lives in a balanced and meaningful way. So wouldn’t it be nonsensical for the play itself to be the very thing that deprives us of balance and peace of mind in our own lives? 3. Art isn’t made in a vacuum, and we have to change when life changes. We’re all familiar with the saying “The best laid plans….” We cannot control the timing of many opportunities that come our way, but we do have control over how we choose to engage with these opportunities. Big Work was originally slated to premiere next month, and at the time we made that decision, both our fall schedules were virtually wide open. Then Kate was invited to teach a course at a local university and I was asked to teach a documentary theatre workshop out of state. Our personal calendars began to fill up as well with things we wanted to be a part of, and during an incredibly honest and thoughtful conversation, we decided that the universe seemed to have a different idea for our timeframe. Could we have taught our classes, stuck to our personal commitments AND produced the premiere of Big Work? Of course. Would we have enjoyed any of it? Probably not. And the only reason we could think to push forward on that timeline was because of the tape that runs in our heads that says we should be able to do everything at the same time, perfectly, and never sweat. Kate and I have always agreed that perfectionism is an ugly master, but we are taught to strive for it and to be silent about the constant sense of failure and deprivation that breeds. We don’t want any part of that anymore. For us, the most important question became: After deriving so much pleasure from the playmaking process so far, would we be willing to push through and sacrifice the joy we are finding in writing this play for the end product of simply producing it quickly? Absolutely not. Our fall is now devoted to the luxurious wide open expanse of exploring the landscape of our play even further and for that we are very grateful. We hope that when March comes around and the play is premiered, that those of you in the audience will be able to not only witness the incredible debates amongst the characters about work and life, but sense our own conversations about how we choose to live and create as artists. *A note to all of the amazing and generous souls who supported our Indiegogo Campaign: our venue transferred our full deposit from fall to spring, and rest assured that every dollar you donated is still going exactly where we said it would – just in March instead of November. We couldn’t be doing any of this without you, and we are forever grateful.

0 Comments

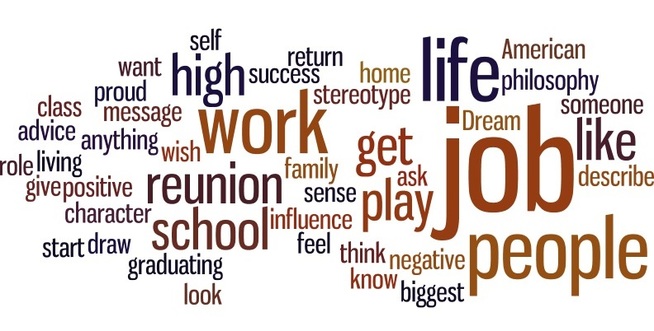

By Kate Ask any writer and they will tell you they become attached to their characters. But documentary work adds another layer to it. When you’ve sat across the table from someone who has opened up to you about their lives, choosing not to include what they’ve told you in the piece you’re writing feels like you are somehow saying her story is less important than someone else’s story. Transforming the 138,097 words from our interview transcripts into Big Work, a 16,000 word dramatic piece, has led to incredibly tough choices about what material to use and what to let go of. Essentially, we could use only 10 percent of the stories we collected in our final piece. Sometimes this meant letting go of a moment or observation we love; other times it has meant not including whole interviewees as characters. And while Melissa and I know having too much good material is a much better problem than not having enough, the cuts have been surprisingly painful. But we can’t ask an audience to sit through a 12-hour play, and the piece as a whole needed direction and cohesion in addition to containing great individual stories. Here is how Melissa and I went about choosing what to include. 1. We asked ourselves, “What is each interviewee’s core struggle with work?” Before we started writing the script, we spent several weeks just reading and re-reading every transcript. While each interviewee shared complex feelings about their jobs in relationship to their lives and their identities, each person seemed to have one thing they were wrestling with above all else. We challenged ourselves to try and name the struggle for each interviewee in one word. When Melissa and I met to discuss the words we had chosen, we discovered that some of the themes we initially set out to examine in relationship to our work – gender, age, immigration status – were too narrow. Instead we saw people, regardless of those labels, struggling with one of four things: to overcome expectations, to realize self-determination, to find balance, or to define their legacy. Naming these struggles not only helped us to understand who our characters are, they also provided the structure for our piece. These themes became the scenes of our play. 2. We eliminated everything that wasn’t directly related to a character’s core struggle or essential biography. There was a man I interviewed from Nigeria who told me so many fascinating stories about what it is like to be an immigrant working in the United States, and particularly the ways he feels an immigrant approaches college differently than American-born students. I loved these passages, and was reluctant to let go of them. But when I started asking myself about what he was really concerned with, it was clearly his legacy. When given the chance to direct the conversation, he spoke about trying to find work that is meaningful and that leaves something behind. He had only spoken about being an immigrant because I had asked him directly about it multiple times. I’m working on a play that asks people how they identity themselves, but I was labeling him and asking him questions that weren’t particularly relevant to his journey. By keeping only what was at the heart of each person’s struggle, we eliminated a lot of anecdotes. But more importantly, we have clearer, richer characters engaged in more meaningful discussions with one another. 3. We looked for characters who offered similar stories. There was no way to include meaningful characters based on all 40 people we interviewed without this being a series and not a single piece (which we considered). After we re-read the transcripts, we found that several characters were wrestling with the same things, had similar biographies, or articulated similar frustrations and triumphs. Melissa and I look at each of those stories and see their value. We see the individuality of the person who told it, and we took a lot away from having heard each one. But for the sake of drama, our global story didn’t need two characters saying the same thing. So we eliminated duplicates, and included stories from only 26 of our interviewees (which admittedly is still a lot). It can be a struggle for Melissa and me as we continue to tighten and hone our play because we know everything that didn’t make it into the final script. There are moments and stories we love that just didn’t have a home here, and we will always know they aren’t there. Hopefully, if we’ve done our jobs, audiences won’t feel those gaps. We’ve had to remind ourselves many times that we can use these interviews to create other pieces, maybe even a couple of 10-minute plays. But while these choices have been difficult, what has surprised us most of all is that we actually found the voice of this piece – really our voices – from the struggle to let go. It made us examine characters in more depth, ask tougher questions, and debate the themes that arose against our original hypotheses of what we would find. Shaping these interviews into a larger story about work and life in America has been an extraordinary journey, and one I wouldn’t trade for anything. We can’t wait for the next phase when we get to have these conversations with our actors, and then with you.  By Kate “HOW CAN I EXPLAIN TO THEM THAT IN THIS WAR, I AM DEFINED BY MY NATIONALITY, AND BY IT ALONE?...THE TROUBLE WITH NATIONHOOD, HOWEVER, IS THAT WHEREAS BEFORE, I WAS DEFINED BY MY EDUCATION, MY JOB, MY IDEAS, MY CHARACTER -- AND, YES, MY NATIONALITY TOO -- NOW I FEEL STRIPPED OF ALL THAT.” – SLAVENKA DRAKULIĆ, THE BALKAN EXPRESS Reading the diary Slavenka Drakulić kept during the Yugoslav Wars made me want to study nationalism. She captured beautifully and painfully how quickly our identity can be sacrificed to circumstance. Granted war is perhaps the most extreme example, but in small ways every day, our desire to define ourselves is in conflict with a world trying to tell us who we are. Religion was not a big part of my life as a child, but I grew up with an extended family that was deeply Catholic and in a town where almost everyone I knew was too. I remember being uncomfortable attending Mass during family reunions, and being told by one relative that I was probably going to Hell. I vividly remember a friend telling me she really struggled with my not being Catholic because “I feel like you are a really good person,” as if being Catholic and being a good person were mutually exclusive ideas. At many moments in my childhood, before I was anything else, I was “not Catholic.” The significance of the label was the otherness implied by those who spoke it. Religion was never a conversation about what I believed; it was one about what I didn’t. In many ways, it wasn’t a conversation about religion at all, and it certainly never extended to what was important to me. Now as a 31-year old woman, I find that the world is quick to label me in other ways – particularly that I am “not a wife” and “not a mother.” The questions I’m asked when I meet new people or get re-acquainted with others are repetitive and unimaginative. Sometimes, it goes further and people assign meaning to why I’m single and don’t have kids. They say I am career-oriented or that I’m selfish and trying not to grow up. Others offer pity or to try to comfort me, clearly ignoring the fact that I’ve expressed no sadness on the subject. Recently, I ran into an old classmate who asked me what was new. I talked animatedly for five minutes about dancing and the play I’m writing. When I finished, he said, “Cool. What else?” I shared a little bit about a recent vacation with friends. He nodded, paused and said, “Anything else?” And then I got it; it was just a less direct way of asking the same questions about a spouse and kids. The funny thing is that these labels – not Catholic, single, childless – don’t relate in any way to how I see myself or how I wish others saw me. To me those things are true, but largely irrelevant to my story. I am a writer – that is how I enter this world. I am a friend nestled in an extraordinary tribe. I am a tanguera. And I am a human inextricably linked to the lives of others. What Slavenka Drakulić was mourning in her journal was the loss of her individuality, of ceasing to be seen for the things that were important to her and instead being reduced to the sum total of what was happening around her. I don’t equate my experiences with hers, but I also haven’t met anyone who can’t identify on some level with that struggle. We measure each other against the way things have been and the way we are told things are supposed to be. We measure each other against the things that we fear and what we hope for ourselves. None of us are innocent of this instinct. But beyond all the real world dangers this can sometimes present, not allowing someone to share how they identify themselves deprives us all of connection. My favorite question we asked during the interviews for our American Dream piece was, “What question do you wish people would ask you?” Some people wanted to tell us about their children, others spoke of their jobs. Some people wanted to expound on a hobby or the trip they recently took. Some wished for an honest conversation about where they are from and how they got here. But by far, most people wanted to be asked, “What are you most proud of?” I’ve thought a lot about it, and the truth is there isn’t a perfect question I wish people would ask me, and I know there isn’t a single question that we’d all universally like to be asked. But my wish is that when someone asks me a question, she does it without a pre-determined idea of what the answer should be. That if she asks about my job or religion or family, she asks because she genuinely wants to know something about me, and not where I fit into her neat schematic of the world.  By Melissa “The highly sensitive [introverted] tend to be philosophical or spiritual in their orientation, rather than materialistic or hedonistic. They dislike small talk. They often describe themselves as creative or intuitive. They dream vividly, and can often recall their dreams the next day. They love music, nature, art, physical beauty. They feel exceptionally strong emotions--sometimes acute bouts of joy, but also sorrow, melancholy, and fear. Highly sensitive people also process information about their environments--both physical and emotional--unusually deeply. They tend to notice subtleties that others miss--another person's shift in mood, say, or a lightbulb burning a touch too brightly.” ~Susan Cain, Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking I am a textbook introvert. For as long as I remember, I favored alone time and small gatherings of close friends to large group activities and over stimulating experiences. I dread small talk and feel anxious at cocktail parties and networking events. I would rather debate the meaning of life with a complete stranger on the subway than talk about the weather with a friend. At the same time, I am an actor and playwright. It's my task to connect with other people, to be able to get inside a character's head, to understand and explore the dynamics of relationships between people. Realizing I was an introvert was a life changing breakthrough for me. But trying reconcile my private self with my very public theatre self? It's been a thought provoking, sometimes challenging journey. It's taken a lot of trial and error to try to balance the two. An introverted artist and a documentary play in the making? It's a recipe for an interesting creative process, to say the least. Before my first interview, my palms were sweaty. It took me a few tries to dial the correct phone number of the interviewee because I was so nervous. I could hear my own ragged breathing echoing back to me from my cell phone. I was sure that when the person picked up, the first thing they would hear would not be my shaky "Hello!" but the very loud beating of my heart. The first few minutes of the interview were a little jerky, like climbing onto a bicycle that I haven't ridden in a few years. I took some deep breaths. I really listened to what the interviewee was saying about their work, about their life. After a couple of minutes, my anxiety lessened, fading into the background. What was left was my authentic, curious self, willing to face my fear of conversation in order to truly witness someone's story. It was as if I had found the perfect gear for my bicycle ride; instead of an effort to converse with the person on the other end of the line, it became a pleasure. Each time I've conducted an interview, I have felt so honored that these friends and strangers alike have trusted me to share such personal details about their lives, their struggles, their dreams. I've felt grateful to be able to connect so genuinely. When I do an interview, I don't do a lot of small talk to start with. Nervous as I am, each call or meeting is like a cold swimming pool. Rather than delay my anxiety and self-consciousness, I dive right in. I believe when we face fear, we are rewarded with courage. It is hard to express how much I feel I've gained both artistically and personally as a result of interviewing so many people across the country for this play. This introvert would rather feel all the anxiety and shyness in the world if it means making a connection with another human being. When I asked one interviewee what question she wishes people would ask her, she said "I want them to do like you're doing. Just really get to know me and it be ok with them." To say that this play has already changed me is an understatement. Susan Cain also says "When you’re focused on a project that you care about, you probably find that your energy is boundless.” I know this to be true. After I end each interview, I can hardly wait to get to the next one, to enter that space where I am really making a connection about something I care so deeply about. When I get to the next interview, and my fear of speaking with someone I don't know inevitably begins to surface, I have the advantage. I know this drill. This happened before, and it will happen again. But for the moment, I begin by taking a deep breath, asking that first question, and trying to be fully present. If I focus on those things to start, I can almost guarantee that I will find myself in that magic moment where both I and the interviewee are vulnerable and trusting. In that space, there's no limit to the connection or insight that can happen. By Kate and Melissa

When we started writing this piece about how our jobs influence the rest of our lives, we knew that we wanted to interview people of all sorts of backgrounds. We just didn’t realize how difficult that would be. We made a dream list. Men and women. College age people, those in their 80's, and everyone in between. People of different faiths. First and second generation immigrants. Middle class Americans and those earning minimum wage. People who lived in cities and those who lived in small towns. White, black, Latino and Asian individuals. With our list in hand, we reached out to our inner circles and canvassed for anyone that might be interested in participating. Then our circles began reaching out to their circles. Word spread. We had a solid start with fifteen interviewees, but after a month, we hit a wall. Our first responders, while diverse in their professions, experiences and personal stories, looked a lot like one another. So we started contacting professional groups for minorities, faith-based organizations, advocacy groups for at-home parents, recreational groups for seniors and nursing homes, groups for people who loved the outdoors, farming associations, and groups advocating for wage increases. We used Meetup Groups, Facebook, Twitter, and email to contact more than 125 organizations nationally, being careful to target rural communities alongside those in big cities. One by one, over four months, we followed each thread, securing interviews in person, by phone, and by Skype until we had forty people willing to participate. We didn’t reach every voice on our wish list, but we got 80 percent of the way there. In some ways, the voices we never reached and why is a story all its own. Here are four things we learned – about others and ourselves – while searching for interviewees. 1. Socioeconomic lines are the toughest to cross. The magic formula: Identifiable + Approachable + Willing = Interviewed. First, there has to be a place where a group of people who represent whatever unique characteristic you are looking to capture gather, online or in person. Once you find where they are, you have to be able to approach them. This means both that there is a means of contact (email, phone number, or a place to physically go), and that it is appropriate to show up. Lastly, if the first two are achievable, individuals have to be willing to participate. As hard as it can be to start a conversation across racial and religious lines, there were places where we could readily identify people by both race and religion, and critically where people self-identified by these characteristics as a point of pride, something that proved critical in a person’s willingness to participate. There were a large number of groups for minority professionals and minority students, and there were both places of worship and social meetups for people of faith that were easily identifiable online. There was almost always a phone number or email address for a contact person, and critically, the contact person was usually a member of whatever community we were trying to reach. When we approached these groups, some were willing to participate and some weren’t. But following this formula, we struggled to reach people earning minimum wage. We realized that people in these professions were primarily identifiable only in two places – their place of employment, where it was completely inappropriate to approach them, and through organizations that provide services to low-income individuals or advocate for higher minimum wages, where the contact person was not representative of the population itself and rarely would pass along our information. On the rare occasion that we identified and approached someone, there were natural fears about why we wanted his/her story, or difficulty scheduling a time to talk. This process underscored what we already knew. As humans, it is incredibly hard to connect in a social way with people across socioeconomic lines. As storytellers, this is one of a thousand reasons why certain voices seem perpetually underrepresented in art. 2. Talking to someone in person is better for connection, but online outreach is more effective for establishing first contact (aka randomly bombarding people at shopping malls is not easy). In order to reach a broad cross section of people, we spent a day “guerrilla interviewing” at a local shopping mall food court, walking up to strangers and asking them if we could talk to them about their jobs. We didn’t expect that everyone would say yes – but we naively thought that because we weren’t selling anything or asking for donations, that people would be curious and join in. Wrong. We encountered fear, annoyance, language barriers, men who engaged with us for all the wrong reasons, and one woman who kept insisting that if we were really playwrights, we’d have something on stage right now. We experienced firsthand what it feels like to walk toward a stranger to talk to them about a cause that matters to you, and see them look away, squirm uncomfortably in their seat or get up and walk away. We realized quickly that most people have their “no” response ready long before they hear what you have to say. We have a whole new respect for anyone whose job involves cold calling or approaching strangers in public for sales or donations. Every time we’ve passed someone on the street since trying to talk to us about the environment or their cause, we smile and nod and wonder how they do it day in and day out. And as two people who aren’t wild about the ways modern technology have eroded in person connection, we had a moment of gratitude for all the ways technology made our interviews possible. But it was also a sad reminder of how hard it is to connect in person with strangers when many people are suspicious and prefer to be left alone. 3. Not everyone is in the middle of an existential crisis. It’s no secret that part of the reason we started writing this play was because, at 30 years old, we were each trying to figure out what our jobs meant in our lives – whether we are what we do, and how work has affected our sense of self-worth and belonging in our communities. It was fueled by a years’ worth of conversations with each other and a lot of friends who were asking the same questions. Many of our interviews lasted 45 to 90 minutes as people shared so much beyond the thirteen questions we asked. Their struggles may or may not have been our particular struggles, but they were struggling none the less. We nodded along thinking, “Yeah, finding your place in the world and finding any balance is really tough.” But then we had many interviews that lasted 10 to 15 minutes. We asked questions about work and people answered in such a straightforward way. The first time it happened, we thought we’d failed as interviewers – that we hadn’t created a supportive place to share. But the more people who told us that they go to work, leave at the end of the day and don't really think much about it in the larger realm of their life, the more we realized that not everyone is in the middle of an existential crisis. We were so grateful for this perspective, and it is essential to the play as a whole. 4. We all carry stereotypes with us, in everything we do. If we are truly honest with ourselves, everyone walks into every situation with the skewed perspective of their own life experiences. And when we started looking for interviewees, we had ideas about things we expected to hear and wanted to make sure we heard. And during this process, we were reminded over and over and over again to check all stereotypes at the door. We were expecting an 80 year-old man to tell us he felt invisible, that the world had forgotten him, not that his best work was being done now. We were expecting an at-home mom to talk about the struggle for parenthood to be validated alongside work outside the home, and instead she wanted to talk about the things she does in her life that don’t involve her child. One by one, each interviewee turned our preconceived notions on their head. We began to wonder, are we just finding all the outliers? Or is this process further proof that each human being has a completely unique story that doesn't fit into a premade box? Maybe we are biased, but we think it’s evidence that in fact, in some way, we are all Visitors.  Melissa and Kate with staff from Storycode Boston and filmmakers of "Good Luck Soup." Melissa and Kate with staff from Storycode Boston and filmmakers of "Good Luck Soup." By Kate Last week, we were invited to talk about our upcoming play on “The American Dream” with the Storycode Boston community. It was amazing to be in a room of people who are so creative in how they think about storytelling, and so generous in offering ideas and feedback. We are so grateful for their warm welcome. And we were really excited to learn about “Good Luck Soup,” a participatory documentary on the lives of Japanese Americans & Japanese Canadians after they left the World War II Internment Camps. Check it out. At StoryCode, we not only got to do the first live reading of excerpts from our interviews, but we also had a chance to share the journey of how we found the people we interviewed. The final piece is based on 40 interviews with people from across the country who work very different jobs and have very different lives. During these interviews, we asked everyone the same 13 questions aimed at getting to the heart of what they do, how they are perceived because of it, and what they want from their lives. Here are the questions:

We saw so many moments of connection, where people with little in common on the surface spoke of similar experiences. Like when a Pakistani-born, female aerospace engineer from the northeast and a white man who works in IT down South shared their passion for work, but also the line they drew for themselves about what they weren’t willing to give up to pursue it. Or like when a 26 year-old African-American woman who works at a housing development and a 56 year-old white female accountant shared their journeys to stop defining success on someone else’s terms. And sometimes, people’s answers were direct contradictions of each other. When we asked people about the advice they’d give high school students, we could almost hear the interviewees arguing with one another even though they weren’t sitting in the same room. We’ve loved hearing their answers to these questions, and we hope that when you come see the show this fall, you’ll answer them too. (Through displays in the lobby, not audience participation. Don’t be frightened!) What question do you think provided the most surprising answers? Leave your guesses in the comments. The Visitors launched their Indiegogo Campaign last week to raise $1500 to help stage this show in October 2015, and are already nearly 50% funded. Find out more and help us spread the word.  A view of Laramie, Wyoming on my road trip from 2005. A view of Laramie, Wyoming on my road trip from 2005. By Melissa When I mention the phrase "documentary theatre" to most people, they look at me a bit confused. I've found that this phrase even causes quizzical looks amongst my fellow theatre artists. I often try to describe it as "theatre based on real events" or even relating to people's knowledge of documentary film to start a conversation about it. Coming from a high school that had no formal theatre program and produced only one musical a year, I first encountered documentary theatre back in my junior year of college during a production of The Laramie Project by Moises Kaufman and the Tectonic Theater Project. The School of Performing Arts cast the show with both actors from our department and with non-actors from the campus community. The result was magic. It was a true community effort. As an actor, I was thrilled to be working with my fellow classmates who weren't performing arts majors, most of whom I had not met before, and many of whom were gay and had experienced firsthand the kind of discrimination explored in the play. We performed several nights of shows together, but more than that, we became friends, allies. I spent hours upon hours in the green room talking to each and every cast member, getting to know them as people, and when our lobby display was defaced on opening weekend with a number of unmentionable phrases and slurs, we found our newly formed friendship became a strong foundation upon which to build a plan for activism. We organized prayer circles, we chalked sidewalks on campus, we planned workshops, lectures, and other interactive events connected with the performances to raise awareness. When the lights came up at the end of the show, the play may have come to an end, but the conversations were just beginning. Getting to work with Moises Kaufman of Tectonic Theater Company (you can read more about his incredible work in the field of documentary theatre here) during a workshop he held for our cast was a rare and wonderful opportunity for me, and I remember being interviewed for the school newspaper at the time about his visit and the play. I was quoted as saying "I'd like to do this kind of theatre someday. It's innovative, and isn't that what theatre is supposed to be?" Looking back on this whole experience, I realize all over again what gift it was. It is my wish that everyone gets the chance to experience something as transforming as this was for me. I still feel this way. A decade later, and I've returned to these documentary theatre roots with this company of my own. For me, in the year 2015, I cannot imagine feeling stronger about a project than I do about this kind of work. We've always needed truth onstage, but now, more than ever, we need to wield performance as a tool for digging into the real stories of our fellow human beings and forging connection. Sinking down below the hum of the major media outlets, going deeper than mainstream offerings, until we get to the very floor of this ocean of human experience. Real human beings with real stories, straight from their hearts and mouths. I have had the privilege of talking to people all over the country, many people from my very own city of Boston itself. After you hear someone's story, it is impossible to look at the world through the same eyes. Riding the subway, chatting with a neighbor, even buying an iced tea from a Starbucks barista feels different. After a documentary theatre interview, I find that my belief in humanity is stronger, that my hope is renewed, that my faith in my community has grown. During this interview process, the world has expanded in ways I didn't know it could, feeling more beautiful and complicated than ever before. At the same time, the world feels smaller and more personal, too. The dozens of people we've talked with across the country now figure in my mind when I think of exactly who my "fellow Americans" are: a man from Egypt studying to be a dentist, a woman approaching her 70th birthday who says her proudest moment is yet to come, and an operating room nurse who believes that it is her mission to help and serve others. I feel grateful for their presence in the community at large, regardless of where in the country they live. I hope that you continue to follow the unfolding of these stories with us, and that if you are able to, you join us in the fall when we unveil this play. Just as The Laramie Project changed the landscape of my life, I hope our American Dream play will change you, too.  By Kate There is a blog I use to read all the time called “Why We Write.” Writers from TV and film contributed posts trying to answer that very simple, yet incredibly difficult question. It’s one I’ve asked myself a lot over the years. I’ve never had any doubt that I have to write. It is often tortuous and often the space where I am most self-critical, but when I don’t do it, I feel like my right arm has been cut off. But that doesn’t answer why, and if you know anything about me, you know that I am obsessed with understanding why. My favorite post in this blog series came from Hart Hanson, and in particular a passage in which he explains that: "I write because I’m totally confused by the world. I never know what’s going on. I absolutely never know what absolutely anything absolutely means…Writing is a way for me to organize the chaos around me. I can corral bits of the sloppy world into a clean white area measuring 8 ½ x 11 inches, where it is apprehensible." I felt an immediate kinship with that passage, and tucked it away. It was a piece of my puzzle, but not the whole thing. My earliest life as a writer was as a penpal with my grandparents. Since the time I could hold a pencil and form my letters, I’ve written to them almost monthly. As I got older, I amassed more and more faithful penpals. To this day, a letter in the mailbox makes my heart leap. And I never read a letter haphazardly; there is ritual to it. When one arrives, it is saved for quiet moment in a quiet place, and it is read at least three times. I’ve always been able to say things to people in letters that I struggle to say aloud. And no matter what is going on in my life, writing and reading a letter is the ultimate comfort. Clue number two. Piece three came in my early 20s. I’d been pretty sick for a very long time with three undiagnosed food allergies. And after 15 years, it wasn’t a doctor who finally put me on the path to diagnosis; it was a friend who read a story in a newspaper and said, “This woman sounds like you.” My whole life course changed that day – not because of medical tests and experts – but because of the willingness of a human to share her story. Knowing that the written word could in fact be healing was another thing I tucked away. The final piece has come to me in the weeks that Melissa and I have been interviewing people for our “American Dream” piece. Recently, I spoke with a man who is an at-home Dad and a volunteer firefighter. When I asked him how he describes his work in a soundbite, he shared great vignettes about the reactions – ranging from condescension and criticism to celebration – that he has gotten over the years to the various jobs he has had. When speaking of the answer he gives to the question now, he said “I read my audience and try to figure out what may start or stop a conversation depending on what I want to do.” When I heard that, I thought, “Yes, that is exactly what I do.” I have seen pieces of myself or my family and friends in every single interview I have done. I have also been taken aback by the differences and left with so much to think about on my bus rides home from these interviews. These snippets of conversation like the one above are not Earth shattering, nor are they critical to our life trajectories or to those of the people who will see this play in the fall. But for me, the people we are interviewing are people whom I would never meet under any other circumstance – strangers who are willing to share parts of their lives with us and with you. And for me, that has as much meaning as anything does. What all of these things have in common – making sense of the world, the comfort of letter writing, being healed by story, meeting and talking with strangers – is connection. I write because sometimes putting thoughts out into the world helps me find the people who have similar experiences. Sometimes it’s a way to find those who really, really disagree with me. I write because in some of the toughest moments of my life, seeing myself in someone else’s story has made me feel less alone. I write because reading and writing have been my greatest teachers. I write because I never get tired of learning about people, and the written word is where I feel most like an explorer. I write because it is my way to connect. When Melissa and I embarked on our “American Dream” piece, we of course hoped that we will ultimately write an entertaining story. But the thing we hope above all else is that some piece of one of these real stories will connect with a piece of your life, the way they have with ours, whether it’s a chance to see yourself in someone else or to be surprised by something new. We hope that when you sit in the audience, you won’t feel alone in a dark theatre, but connected through shared experience and, of course, through story.  By Melissa "What do you do?" How many times have you been asked that question? How many times have you asked it of others? When greeting an old friend, when meeting someone for the first time – it seems to be the go to question when we don’t know what else to say. There is nothing inherently wrong with this question, but something about it has always bothered me. It seems so…narrow. It is almost always answered with a short, simple response. "I'm an accountant." "I'm a lawyer." "I'm a teacher." "I'm a waitress." It starts to feel like all we are. Whenever I hear myself start to say "I'm an administrative assistant", I try to catch myself and edit my response. "I work as an administrative assistant." Somehow tweaking a few words in my response seems like a good place to start. But after that? How do we dig deeper into who we really are, especially with someone we may have just met? Kate and I started to talk about this with our friends, and it was like we hit a nerve. Everyone had a story to tell – about feeling like their job was all they were and about struggling to find the words to express who they really are. One question that also came up was "If I don't ask people what they do for a living, what other questions could I ask?" In a way, exploring this question is like inventing a new language. If our own circles were so eager to talk about this, we figured others would be too. At the end of February, we started researching and interviewing people for a play about “The American Dream,” our relationships to our jobs and how it affects the rest of our lives. We’ve spoken to over two dozen people across the country already, and feel very struck by how eager each person has been to try and get past the "What do you do?" question. Each person we've talked to, regardless of their job, has had different ideas about how they'd like to connect with other people in their lives, and many of those ideas are independent from what they do for work. The more people we talk to, the more we hear the desire to break free of our "work identity" and re-imagine the way we connect with the people in our lives. It feels like charting a new course on a map we have always used. We are still interviewing, still unpacking all the things we are hearing. But we know this: people are ready to continue this conversation about changing how we identify ourselves and how we connect with our community. It's a challenge but it's exciting. Change is in the air. It's time. Leave a comment below and tell us: What do you say when people ask "What do you do?"  By Melissa and Kate Have you ever had a moment where someone told you his or her story and you saw the world in new way? Or seen your own experience in someone else’s story and suddenly felt less like a Visitor? We live for these moments. We are Melissa and Kate, and we started this documentary theatre company to find and tell those uncommon, real stories, and to build a community where we can witness them together. In our experience, the theatre is a place for connection and truth, and we hope to create a space onstage and online that is rooted in those values. Every two weeks, we’ll put up a new post to share inspirations behind the original works we create, reflect on the role of theatre arts in our community, and start a conversation about the uncommon experiences we all share. We hope you’ll be readers, but much more than that, we hope you’ll add your voices to the conversation. Sharing your story can change minds and foster connection. So bring your humor and your silliness, your honesty, and most of all, your stories. The question that started this whole endeavor for us was, “Where in your life do you feel most like a Visitor?” We can’t think of a better way to start this blog then by asking that question of you. We invite you to leave us a comment below or let us know through Twitter or Facebook where you feel like a Visitor. Let’s get a conversation started. |

ARCHIVES

July 2016

WHAT YOU'LL FIND HEREStory inspirations. Artist reflections. Community conversations. CATEGORIES |

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed